Oyster Reefs as a Climate Change Adaptation

This and other work from educators in our 2022–23 Climate Resiliency Fellowship

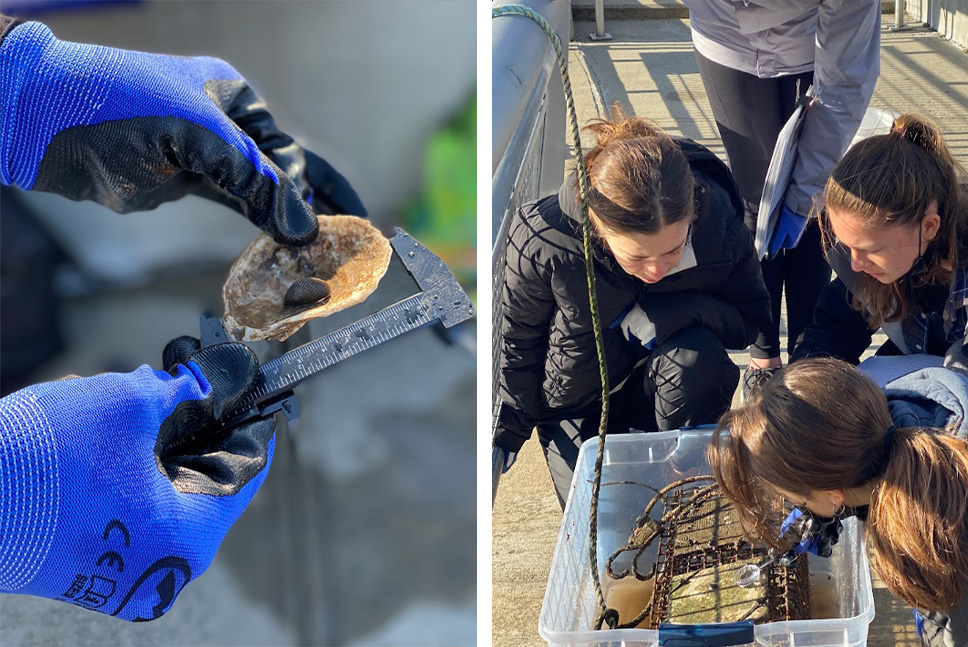

If you walk along Manhattan’s East River near East 90th Street and time it right, you’ll see high school teacher Tim Clare and a group of his students pulling a trap out of the water and onto the dock. The cage is full of oysters, and it’s actually a field station for studying the concept of living breakwaters. “Oysters are really incredible, and over time, they are able to generate reefs that can begin to break up wave action, storm surge effects, and improve water quality,” explains Tim. At a large scale, oyster reefs could be a nature-based approach to address the impacts of climate change along the shores of New York City. Tim’s students are studying this possibility hands-on, both with the East River field station and with a tank back in their classroom, monitoring oyster growth and water quality, and keeping a close eye out for oyster babies, a sign of health.

Tim was one of the teachers in this year’s Climate Resiliency Fellowship, a year-long professional learning program for educators looking to advance their ability to teach for climate action. In gatherings facilitated by Shelburne Farms Institute for Sustainable Schools staff, fellows get the chance to connect, collaborate, and get support from peers; to draw inspiration from invited speakers ranging from artists to climate scientists; and to have dedicated time to work on their own projects. For Tim, the last year offered the space to redesign his science elective course as a cross-disciplinary class in which students could envision climate solutions.

The program, participants say, is transformative, not just on their skills as educators but on their mindsets, moving them from “doom and gloom” to hope and empowerment. “This fellowship has re-energized and re-focused my attention on climate change…It has deepened my commitment to inspire my students to take action,” says teacher S’ra DeSantis. In the words of another participant:

This fellowship has shown me that climate change is so much more than scientific facts. Helping people understand and cope with climate change is actually a way to build community, be empathetic, express creatively, generate hope, connect with values, move toward equity, build resilience, and empower many voices. These ideas come from the many conversations, exercises, and thought processes inflated by the fellowship. The program has opened a new world of core education ideas for me.

Read on for a sampling of inspiring work from this year’s fellows.

Kathryn Buckley, middle school science teacher in Holliston, Massachusetts

Her focus: Filling in the gaps from science to action. “The main questions I really wanted to try to get through with my kids this year were, how does climate change affect us? Why does climate change matter? How do we translate knowledge to action? And, I really wanted to integrate the Massachusetts Science Standards into the study of climate change.” (By spring, she’d done just that.)

What students did: Kathryn’s students started with making a personal connection. Students mapped landmarks they’d visited in Boston; then, using interactive tools like the Climate Ready Boston Map Explorer and NOAA Sea Level Rise Viewer, they made predictions about how the area around their landmark might be impacted by climate-induced flooding or extreme heat, and how those impacts might unequally impact marginalized groups. “We’re not just asking, how is Fenway Park going to be flooded, but what does climate change mean for vulnerable populations like the elderly or children? The lesson is a way to get them thinking about the ramifications of climate change.” From there, students moved into designing Boston’s future, assuming the role of city planners and teaming up to offer strategies to address issues like rising sea levels. Students also dug into the chemistry of climate change with hands-on labs focused on molecular motion (“I wanted them to know, what’s so special about CO2?”), heat transfer, and ocean acidification.

In her words: “In this fellowship, it really felt like I found my people. This work is the culmination of thirty years of teaching.”

Don Taylor, middle school humanities teacher in Montpelier, Vermont

His focus: Three years ago, Don started a sustainability program at Main Street Middle School, with input from students and the community, via the Cultivating Pathways to Sustainability program. “My goals coming into the Climate Resiliency Fellowship were to develop and formalize a local ecosystem of community partners, to develop leadership training for our youth partners, and to communicate regularly about what we were doing.” In partnership with the nonprofit UP for Learning, Don’s students have since developed a youth leadership module and facilitated conversations for their classmates around sustainability.

On his approach: “I don’t like to use the words, ‘fight climate change.’ Instead, I say we’re trying to create a sustainability movement.” Over the last year, that collaborative movement has looked like students cooking and donating food to the local food pantry while learning about the connections between climate change and food insecurity; studying fast fashion and fiber arts; and collecting climate data around maple sugaring and local agriculture.

In his words: “Teaching climate change is tough. It gets pretty dark, pretty quickly. So, we’re working on hope and having fun. We eat together, we cook together, and we’re trying to find a purpose and stronger links between our projects, sustainability, and climate. Students are empowered and working on the issues that come up.”

Lindsey Collins, high school English teacher in San Francisco, California

Their emergent work: Lindsey’s project bridges climate crisis education and queer studies, fueled by a growing sense of urgency. “When I started thinking about this project last year, I could have never foreseen that there would be, now, over 400 bills targeting LGBTQ youth and adults. Against a backdrop of climate despair, LGTBQ+ students are experiencing an ongoing mental health crisis.” Lindsey’s hope is to create a workshop that supports educators in teaching LGBTQ+ resilience and climate resilience as interconnected.

The role of natural places: In developing this workshop, Lindsey’s goal is for queer students to feel seen by their teachers—and for queer students to feel safe in nature. As they describe it, an antidote to despair is seeing yourself in natural places. “The concept of ‘queer ecology’ advocates for and facilitates traditionally excluded groups’ immersion in wild landscapes and climate science,” explains Lindsey. “Teaching students to be able to see themselves in nonhuman places and to feel seen by those places and to connect with them will give educators and students a sense of agency and ownership of the unique power of LGBTQ+ identities to shape our futures.”

In their words: “It’s not just that queer people need inclusion; it's also that queer people and perspectives are vital to our collective survival.”

Muriel Stallworth, PreK–8 art teacher and sustainability coordinator in Brooklyn, New York

The work of systems thinking: “Our plan has a very lofty goal: that over several years, we’ll change our school culture,” says Muriel. “We want to offer fellow educators ideas of how they can focus on systems in their curriculum, to help kids understand how the world is made of systems, whether they’re natural or social, and how regenerative systems are better than non-regenerative systems.” To date, Muriel and a teammate have held three school-wide presentations to advance this type of thinking and reflection, and are now working with their school’s curriculum coordinator to shift all units to incorporate systems and demonstrate interconnectedness.

Food as a hook: “Everybody relates to food,” laughs Muriel. They used food to advance sustainability at their school by starting a food donation program: At the end of every school day, uneaten cafeteria food is donated to a local organization addressing food insecurity. Today, thanks to composting and this new donation program, the school has zero food waste. This is the type of work they say is “above the water line,” meaning it’s visible and relatively easy to implement. “But we want to go deeper,” explains Muriel. “We want kids and teachers to really get involved to the point that they make lasting meaning. To engage people in reimagining the future.” The team finished the year by piloting a hydroponic garden tower; the greens it produced were shared with a smoothie-tasting party. Next year, the tower will be used around the building to support units like learning about plant lifecycles.

What’s next: The work of curriculum transformation will continue, and plans to establish a school garden are underway. "We want to intentionally integrate this work into the school curriculum, and acknowledge and deal with emotions surrounding climate issues."

Amey Bailey, Hubbard Brook forest technician in Woodstock, New Hampshire, and Jess Boynton, 6–8 science teacher in Sanbornton, New Hampshire

Their project: Jess, a classroom teacher, collaborated with Amey, a community partner, to establish schoolyard forest plots, allowing students to collect climate data just steps from their school door. “With a forest plot, you can have your students become forest ecologists,” explains Amey. “These permanent plots became outdoor classrooms where students can ask questions and design methods to study the life of a forest, building on data each year.” In quarter hectare areas, Jess’ students track everything from tree size and tree health to soil temperature, erosion, snow height, wildflowers, and insects—and think about how forest health will change as the climate changes.

The role of wonder: “Every time any of my classes go outside or do a lab, students record things they’re seeing, noticing, and wondering,” says Jess. In the classroom, students look at weather data, record in their journals what they notice before events like rainstorms and snowstorms, and discuss connections between weather and climate. Students also learn chemistry through the lens of photosynthesis, and talk about carbon storage in trees.

In their words: “I feel like our progress toward addressing climate change will be so much better off if our kids have relationships with the outdoors and understand that it can be a good place to learn,” says Amey. Adds Jess, “My main goal is to integrate climate into all the things we’re learning so that, by eighth grade, students have common language and really ‘get’ climate change. When they move to high school science classes and do more climate work, they’re familiar with the concepts.”

Ed Robbins, high school science and woodshop teacher in Plymouth, Vermont

His goal: “To integrate climate change education into the woodshop and into my chemistry class—chemistry was a lot easier,” laughs Ed.

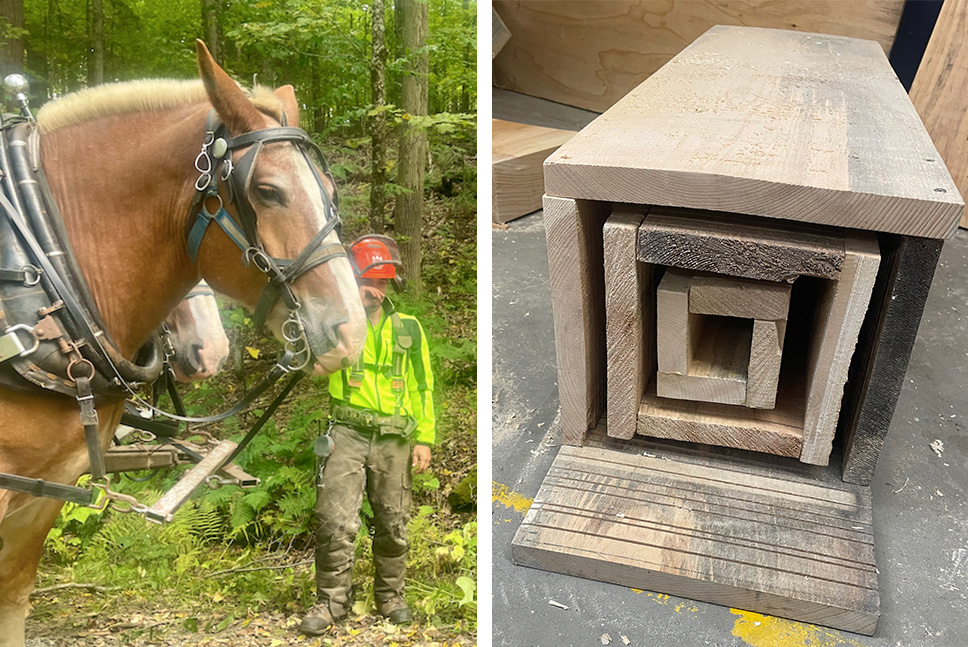

Unlikely connections: Ed’s woodshop class took a field trip to Marsh-Billings- Rockefeller National Historical Park, where they heard from wildlife biologists about the devastating impacts of white nose syndrome on Vermont bats. “The connection with climate change was, how can we help nature bounce back from the white nose syndrome?” explains Ed. To answer that question, students made four bat boxes back in the woodshop, which were posted around the school and at Marsh-Billings to support the bat population. And in Ed’s chemistry class, each student chose two climate solutions from Project Drawdown, then ran data models to see what kind of positive impact their proposed solutions might have on CO2 levels.

In his words: “As a chemistry teacher, I try not to be preachy about climate change and just present them with the data. How are you going to interpolate this? How are you going to figure out what’s going on with this data?”