Sustainability’s Big Ideas Help Teachers Address Climate Change

Guest blog by Anne Bijur, educator

Teachers are under enormous pressure to help children be successful in our increasingly interconnected, complex global society. And they're teaching in a climate that often makes them fearful of tackling difficult or sensitive concepts in the classroom.

Shelburne Farms professional development programs encourage teachers to surmount these challenges. Our concrete tools and frameworks that focus on natural and social sciences, inquiry, and hands-on exploration of real-world problems help teachers help students grapple with whatever future they might face.

More and more, climate change looms in that future. So at this summer’s Education for Sustainability (EFS) Institute, we shared resources developed by our Sustainable Schools Project, especially the Big Ideas of Sustainability, to help teachers develop climate literate students.

CLIMATE LITERACY:

Understanding your influence on the climate and climate's influence on you and society.

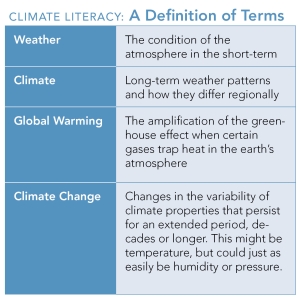

According to NOAA, the National Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, climate literacy is an understanding of your influence on the climate and climate's influence on you and society. The EFS Institute was fortunate to have Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux, Vermont State Climatologist, help boost our climate literacy quotient.

The climate is a system with multiple interconnected parts. As a climatologist, Lesley-Ann is concerned with changes over time within this system. These concepts, Place, Systems, Interdependence, and Change Over Time, are four of the twelve Big Ideas of Sustainability that form the scaffolding for how to educate for a sustainable future. If students can imagine the different parts of a system in their own community and how those parts are connected, they will be better able to anticipate how this system might change over time— and how to prepare for those changes.

Here’s an example. Students might notice that their favorite swimming hole is very shallow this summer and connect that with the drought we are experiencing in Northern Vermont. They might wonder how the lack of water will affect local farmers and the fall harvest. They go apple-picking and learn that the drought has led to smaller and fewer apples on the trees, which means less profit for the farmer and less of a need to hire migrant labor. They wonder, are we having dry summers more frequently or is this an anomaly? Are there drought resistant trees that will grow in Vermont? More efficient irrigation systems? They organize field trips to visit a local orchard and UVM Extension to meet with scientists researching apple tree varieties.

We believe that giving students experiences with one system, the global climate, will encourage them to look at other systems, like the food system or their local government, with a similar sustainability lens. Stay tuned as we follow the educators from the EFS Institute and the creative ways they use sustainability concepts to teach climate change over this coming school year.

Some of our veteran teachers are already demonstrating success in creating climate resilient schools. With support from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Vermont Energy Education Programs, Shelburne Farms compiled case studies on four Vermont schools engaged in climate change education, focusing on resilience and adaptation. Burr and Burton’s Mountain Campus exemplifies the ideal of place-based education. A LEED certified building, constructed with local timber and stone, the campus is net zero energy - meaning it derives all its energy on-site through solar panels and wood. Students get hands-on experience monitoring the systems required for the campus to meet all its energy needs using local resources, one of the keys to climate resilience.

At the Edge Academy at Essex Middle School, students directed their own learning about climate and the Big Ideas of Sustainability. They chose to explore maple sugaring and along the way learned some ways the climate was influencing their lives and that of a beloved Vermont industry. While pondering questions of location, seasonality and the effects of temperature on sap production, they designed and built a functional sugar house.

In another project at the Edge Academy, students examined the impacts of car idling. Using a systems approach, they showed how small local choices (whether to take the bus, ride your bike or turn off your car while waiting for family after school), can have larger implications for air quality, climate, the atmosphere, and community health and well-being.

Teaching about climate change is complex and challenging, but the questions that students come up with during the process provide for rich discussions and bringing in the Big Ideas of Sustainability helps provide context for why these difficult conversations are important to the future of our world.