Why not find some ways to bring horse activity back into the barn. That is what it was originally about.

Breeding Barn Rehabilitation Progress

Joe Cotter and Adam King carefully position a restored window into a dormer that’s 35 feet above the Breeding Barn floor. You can’t be afraid of heights and do this job, that’s pretty clear. And they’re repeating this feat across all eight of the large dormers in the building, working from staging and lifts. They both must have ice in their veins. Given that they worked into November, that might be true!

Joe and Adam are part of the team of restoration carpenters helping the Farm with the latest phase of work on the Breeding Barn: repairing the windows and associated woodwork above the building’s roofline. This project began with an assessment of the woodwork in 2015. By next spring, we’ll have repaired all but the center lantern and two large dormers at east and west ends of the barn.

Since Shelburne Farms acquired the Breeding Barn from Shelburne Museum in 1994, the barn has been a “work in progress.” Lots of work. Lots of progress. It has needed a great deal of TLC simply to shore up its roof, walls, beams, and foundation.

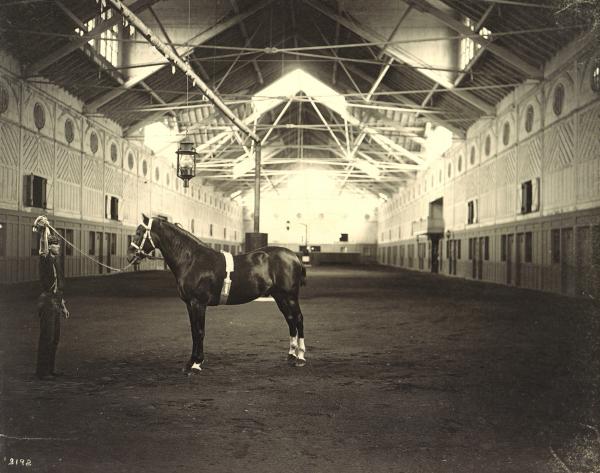

That’s not surprising for a structure of its size and age. It was built in 1891 and was the largest open-span wooden structure in America until 1939. For many years it stood as a benignly neglected behemoth.

The enormous scale of the work has meant prioritizing and phasing in only what’s critically needed to stabilize this magnificent building – and to ensure its future.

Perhaps the most visibly dramatic work was done shortly after we acquired the building. In 1997, workmen installed two acres of copper on the roof of the barn, replacing a leaking and failing shingled roof. Not long after, workers installed a fire suppression system. More recently, engineers carefully assessed the condition of the barn’s structural elements – its beams, stone wall foundation, and the composite (iron and wood) trusses that support the roof. Where original materials were deteriorated or simply missing (there were many such places), framers and masons made repairs.

What is easy to sum up in one paragraph has, in reality, taken many years, many skilled craftsmen, and for much of the time, the leadership of architectural conservator Doug Porter to complete. What’s at stake is the survival of a critical swatch in the fabric of this National Historic Landmark.

“The Breeding Barn is the principal building of the Southern Acres portion of the Farm, and it was famous at the time of its construction,” Doug points out. “The windows in the eight large dormers and lantern, which provided natural light for the riding ring, are among the key characterizing features of the building. The Farm has taken a unique approach to their repair and conservation,” he says.

Down from the staging, Joe and Adam duck into the Breeding Barn’s annex, which has been temporarily retrofitted to serve as a carpenter shop. “By allowing us to set up a shop in the barn,” Doug offers, “the Farm will come to own the machinery and tooling for maintaining the windows in the future.” Here is where the crew, including Doug and restoration carpenter Mike Cotroneo, does the painstaking work of repairing the windows that they have removed from on high.

“Most of them were in trouble,” Mike explains. “Some windows just fell apart in our hands.” He points to some of the horizontal and vertical wood sash elements in one window that he’s restoring. These components in particular, he says, “take a beating.”

The crew reuses the safety glass in each window, and replaces decayed or punky pieces of the original white pine sashes with new pieces milled from the same species. To replace damaged sills and molding, however, which bear the brunt of the weather, the crew uses more durable hardwoods. This will help extend the life of the windows and frames, as will regularly painting the wood moving forward.

To mill replacement pieces for the windows, the team carefully replicates the mortise and tenon joinery and molding shapes that are characteristic of the original windows. “It’s a lot of work,” Mike admits. And sometimes tedious.

But it has its rewards. “It’s such an iconic building in a beautiful spot,” Mike says. “The amount of detail that’s in the building is amazing. Even up where no one can see it.”

The work also holds a few surprises. Although the building was constructed based on clear blueprints, it turns out that not all the dormers are the same. “I think they had different crews on different windows,” Mike muses, “because some of the dormers are constructed differently. That’s kind of fun.”

And working inside one dormer this fall, the crew uncovered some detailed illustrations penned into one of the boards (see photo below). Sadly, the story behind these drawings is lost to time. (The crew put the illustrated boards back in place.)

To date, Doug and his team have completed restoration on six of the large dormers (three on the south side and three on the north). They’ll tackle the remaining dormers and the barn’s lantern next year. By 2019, this window phase of the building’s rehabilitation will wrap up. The shell of the building will stand sturdy and strong.

But what will imbue new life into the magnificent historic structure? The Farm continues to consider how best to make use of the Breeding Barn. At minimum, it will be more regularly used as seasonal gathering space for educational, agricultural, and community events -- like the 4-H cow shows it hosts currently, or the annual choral celebrations of All Souls Interfaith Gathering. Shelburne Farms President Alec Webb sums it up, “The only way historic structures can continue into the future are to become part of the daily life of the community.”

Mike likewise takes the long view. “This place is so amazing. It’s a great asset for the community.” And barns in general, he argues, “are part of our heritage. They’re works of all the labor and thought that went into them.”

All the rehabilitation work on the Breeding Barn has been made possible thanks to generous gifts and grants.