Studying Climate Change Through Birds & A Sound Map Activity

It’s amazing what you can hear when you sit still outside and listen deeply—a bird you’ve never heard before, flying overhead on a migratory path, or the drone of a bee on a flower. As an amateur birder, educator Camie Thompson already appreciated how much you can learn from listening quietly. But it wasn’t until a “sit spot” exercise at Shelburne Farms during the Climate Resiliency Fellowship program that something clicked. “I had found the idea of teaching climate change, a massive topic, daunting. This fellowship experience made me realize, why can’t I integrate something I love—birding—into my teaching? Why put climate change in a box?” says Camie.

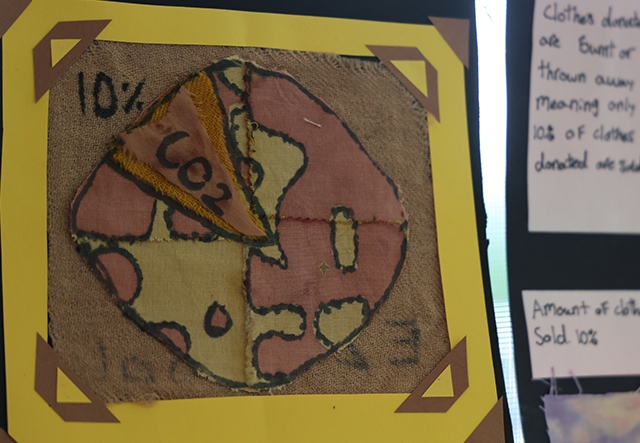

This past year, she designed two units for middle and high schoolers at the Lake Champlain Waldorf School that used ornithology as a lens for learning about climate change and local ecology. Students spent time each week in the woods, carefully listening to and observing the animals and plants around them. Their curiosities drove classroom discussions; students learned about how warming trends are actively changing migration patterns, egg laying, and even the bodies of some bird species. “They noticed that they heard certain birds and saw different plants at different times of the year compared to when they were younger,” explains Camie. “Those observations really opened Pandora's Box for us to talk about the environmental factors causing these shifts.”

This past year, she designed two units for middle and high schoolers at the Lake Champlain Waldorf School that used ornithology as a lens for learning about climate change and local ecology. Students spent time each week in the woods, carefully listening to and observing the animals and plants around them. Their curiosities drove classroom discussions; students learned about how warming trends are actively changing migration patterns, egg laying, and even the bodies of some bird species. “They noticed that they heard certain birds and saw different plants at different times of the year compared to when they were younger,” explains Camie. “Those observations really opened Pandora's Box for us to talk about the environmental factors causing these shifts.”

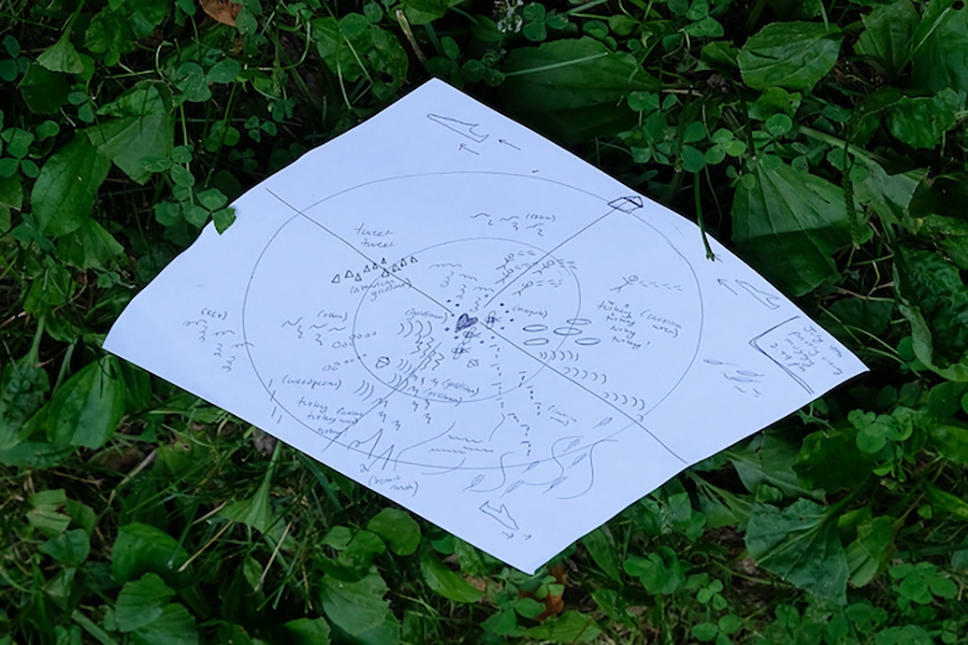

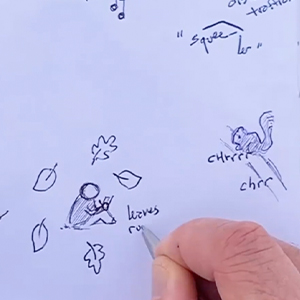

Camie’s students practiced a number of nature journaling techniques to get to know the landscape. One of these techniques was sound mapping: drawing visual representations of every sound they heard, from bird calls and wind to distant sirens or airplanes in flight. The challenges with sound mapping are to stay present and to resist identifying bird songs with a field guide. During sound mapping, you simply record what you hear with a symbol or descriptive phrase, not necessarily a proper name. After making their maps, Camie’s students discussed their observations and compared what they heard. She pushed them to develop a shared language to refer to the animal sounds on their maps, inspired by the teachings of Indigenous scholars Judy Dow and Robin Wall Kimmerer (see Kimmerer’s essay, The Grammar of Animacy). Occasionally, to solve a debate, she’d reveal a bird’s common name, but mostly Camie “allowed students to sit with their wonder.”

Down the road, Camie would like to connect this type of nature journaling to larger citizen science endeavors so that students could put their observations into the context of regional patterns. “I consider these units as starting points for the future,” says Camie. But there were, she says, some meaningful successes from year one. “I found that being outside made a difference in students processing their climate grief. Our discussions were more thoughtful and regulated the more time I gave them to be in the woods. Students also seemed to really understand, some for the first time, the ephemeral nature of wilderness—that you may hear or see something one day but not the next. And I noticed kids paying more attention to birds, even at times when they weren’t in class. That’s a seed that’s been planted, I hope, for life.”

Get to know your place by making a sound map! Try the activity yourself, or with a group of students, as outlined below.

Activity: Make a Sound Map

For materials, you’ll need a writing utensil and something sturdy to write on, like a journal or paper and clipboard. Depending on your place, you might consider bringing something comfy to sit on while outside, like a yoga mat or cushion.

Camie notes this activity is accessible for learners of all ages, in any setting. “You can do this anywhere, not just in the backcountry,” she says. “Any sound that you hear is a good sound. It’s OK if there’s not a plethora of birds or a gorgeous cacophony of sounds! It could be that you hear the humming of a street light and a nearby cicada. That’s a perfect, real sound map that tells you something about your place.”

Instructions

- Head for the outdoors! If you’re doing this activity in a group, circle up to prepare.

- To prepare your ears: Practice mindful listening for a minute. Sit or stand straight with both feet or sit bones firmly planted. Either close your eyes or soften your gaze, and turn your attention to your ears. What’s catching their attention? Listen to what’s ahead of you, what’s behind you, to the right, and to the left. Now try tuning out any human-made sounds you hear, and instead focus on non-human sounds. Finally, push the boundaries of how far you can hear. How many miles away can you hear? What can you hear that is close by?

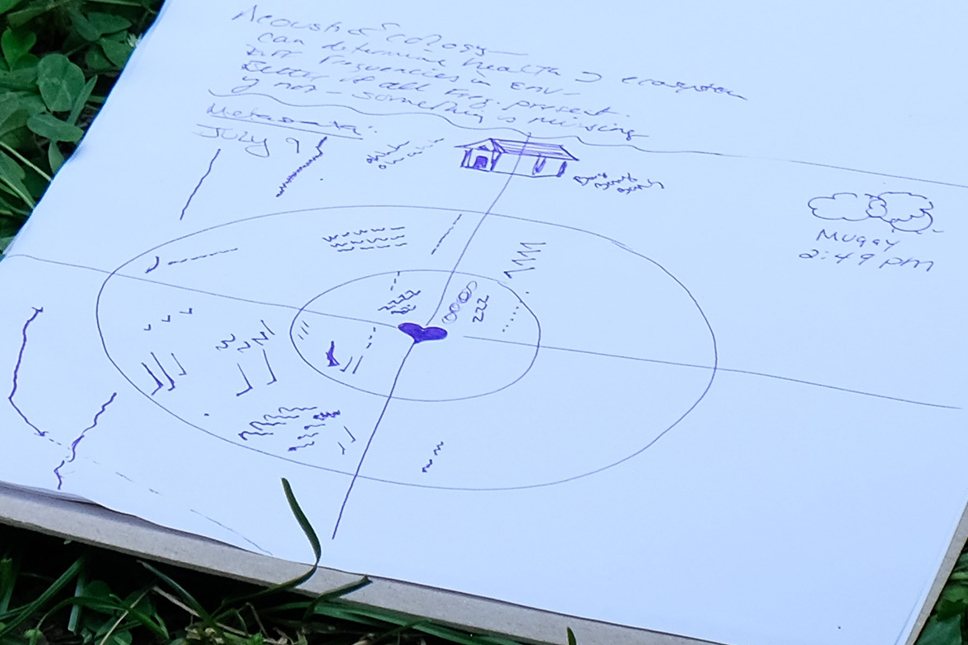

- To prepare your sound map: Orient your paper horizontally. At the center of the paper, draw a symbol that represents you—a stick figure, an “x,” a heart, whatever you like.

- Draw two concentric circles on your paper around you, like a bullseye. These will represent the outer, middle, and inner periphery of what you can hear.

- In one corner of your paper, record your metadata: your name, location, time, and any other relevant factors for your observations like wind or temperature. In another corner of your paper, or on the back, draw a box; this will contain your map key. Your map is ready to be filled!

- Head for a spot where you can sit comfortably for as much time as you can permit—we suggest a minimum of 5-10 minutes, though the longer you sit, the more rich your map will be. If you’re doing this activity in a group, have students sit a distance away from others to minimize distractions, and ask all participants to face the same direction, toward a landmark or cardinal direction. This will help guide the group discussion later on.

- Once seated and settled, start a timer and listen silently with your ears “open,” as practiced earlier.

- Record each sound you hear on your map, relative to its position to you, with a symbol, doodle, or nonsense nickname of your choosing (at right, an example from John Muir Laws). Resist the urge to identify creatures by name. Each time you hear a new sound, add it to your key with a description of what you heard. Use the same symbol for repeated sounds.

- Once your timer goes off, take a look at your map. If in a group, come together to compare and discuss your findings. You might discuss: What do you notice about your map? How do your maps relate to one another? Did we hear any of the same things? Different things? Are there any commonalities in the personal languages you created? Which Big Ideas of Sustainability are alive in our place?

Thanks to Camie Thompson for sharing this activity with us. Camie would like to also credit the following individuals and organizations for their influence: Bridget Butler, Judy Dow, John Muir Laws, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and the Willowell Foundation.

Apply to join a future cohort of the Climate Resiliency Fellowship! This program will next be offered in 2026–27; sign up for our educator emails to be notified when applications open in 2026.