It's so true that the SF property, as designed by Olmsted, "a balm for the human spirit". We considered moving out of state last year, but one of the major reasons why we decided to stay and continue to be stewards of SF is our proximity to it and being able to walk through its forests, meadows and wetlands.

Olmsted's Vision at Shelburne Farms

This blog was originally published by the National Association for Olmsted Parks in their "Spotlight" series, in honor of the ongoing Olmsted 200 celebration. The original piece, along with information on Olmsted 200, can be found here.

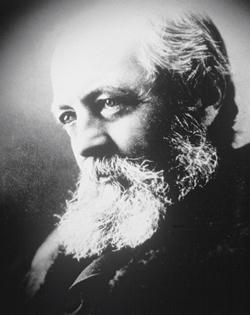

– Frederick Law Olmsted to Charles Eliot, July 20, 1886 (Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Collection)

Shelburne Farms is an education nonprofit working to inspire and cultivate learning for a sustainable future. Our campus, a 1,400-acre working farm and National Historic Landmark designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., makes that work a lot easier. The themes and beliefs that run through all of Olmsted’s projects: that nature is a balm for the human spirit, and that access to nature is essential for all, are evident at Shelburne Farms, and the landscape he inspired here is fundamental to our educational mission.

Shelburne Farms’ campus was once the agricultural estate of Lila Vanderbilt and Dr. William Seward Webb. Between 1886 and 1902, the couple bought 32 farms on Shelburne Point, amassing 3,800-acres framed by the blue waters of Lake Champlain, the tumble of the Adirondacks, and the rolling Green Mountains of Vermont. It was an ideal canvas for Olmsted.

Olmsted visited Shelburne Farms in June of 1886 and offered ideas on the function and design of the assembled property and its future buildings. Within a year of visiting, his original plan delineated a division of the property into farm, forest, and parklands (or park), a plan that was modified and carried out by Dr. Webb and Farm Manager Arthur Taylor.

In addition to this organizing concept, Olmsted borrowed design principles from the English naturalist landscape tradition of the early 18th century, whereby parks were built around three elements: broad meadows, diverse woodlands, and water reflecting the sky. All of these features were–and remain–abundant at Shelburne Farms.

While Olmsted’s involvement at Shelburne Farms was brief, his imprint here is unmistakable, and his vision and ideals even more relevant in today’s world. How fortuitous that when the education nonprofit was formed in 1972, this landscape became its campus for learning, as a way to connect educators, students, and visitors to the natural world, just as Olmsted intended. And since the pandemic began nearly two years ago, this place, designed so intentionally to offer solace in nature, has provided that for countless visitors.

Comments

Holly, Thanks for posting this. I've often wondered, while exploring the estate, are there any of Olmstead's designs of the original plans for the land? That would be so interesting to see.