Climate Action and Food Waste: One School's Story

A case study in empowering students—and reducing waste—from Norwich, Vermont’s Marion W. Cross Elementary School

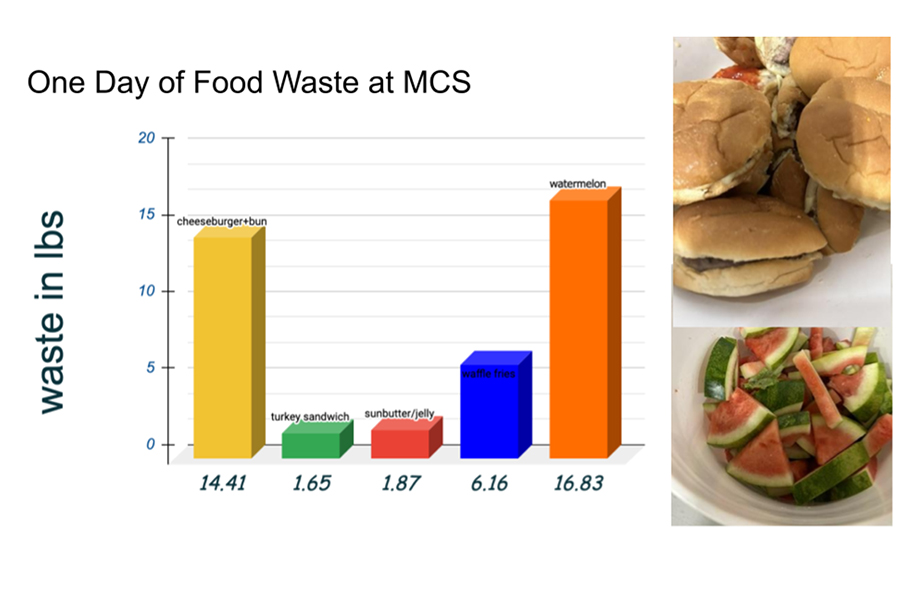

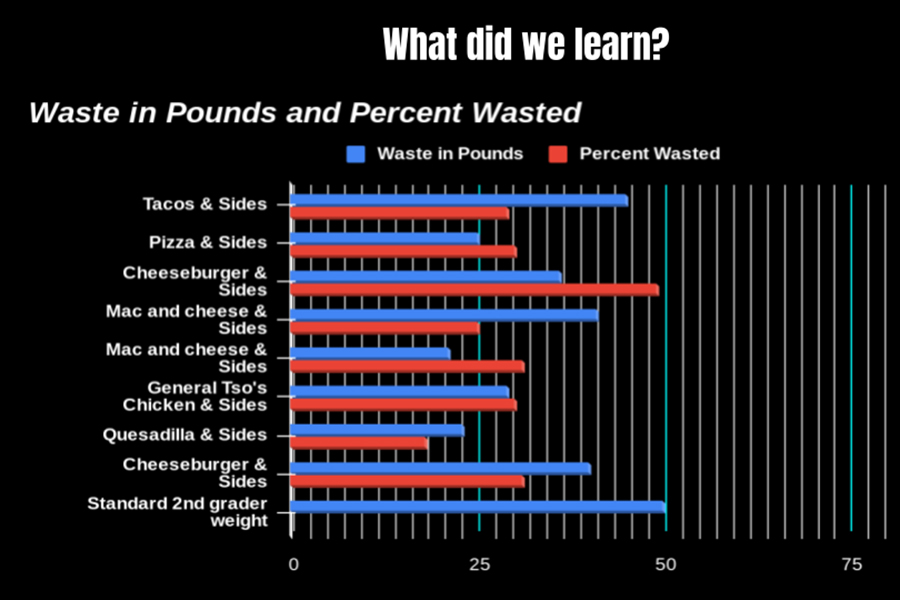

Sixteen pounds of watermelon. Fourteen pounds of cheeseburgers and buns. Six pounds of waffle fries. This, students calculated, was the amount of food waste generated during a single lunch period at Marion W. Cross Elementary School. On average, each lunch service resulted in 33 pounds of food waste. “That’s only slightly less than the weight of one second grader,” says a fifth-grade student.

America throws away almost 40 percent of its food supply each year, with major environmental consequences. If wasted food goes to the landfills, it produces methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas. The production of this wasted food generates the equivalent of 32.6 million cars’ worth of greenhouse gas emissions every year.

America throws away almost 40 percent of its food supply each year, with major environmental consequences. If wasted food goes to the landfills, it produces methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas. The production of this wasted food generates the equivalent of 32.6 million cars’ worth of greenhouse gas emissions every year.

In food waste, the students, staff, and administrators of Marion Cross found an opportunity to take meaningful climate action. “For kids to feel empowered that they can actually do something about climate change is super important,” says Chrissy Morley, environmental and experiential education coordinator at Marion Cross in Norwich, Vermont. “If we use food as a way of empowering kids to be part of the change that we need to see in the world, we’ll have young people that feel like they have some agency.”

In her role, Morley brings K–6 science standards to life through all kinds of experiential learning, including learning in the school’s sugarhouse and garden, pictured here. “I already knew that teaching with food fosters connection—with the living world, with the curriculum and across disciplines, and with each other and the wider community,” says Morley.

In her role, Morley brings K–6 science standards to life through all kinds of experiential learning, including learning in the school’s sugarhouse and garden, pictured here. “I already knew that teaching with food fosters connection—with the living world, with the curriculum and across disciplines, and with each other and the wider community,” says Morley.

Morley and teacher Devin Burkhart used food waste to involve their students in advancing a district-wide climate action plan. “Kids don’t have a lot of power over what kind of vehicles their parents drive or what kind of windows or insulation go into our buildings. But what does involve kids is food,” says Morley.

Below are the steps that Marion Cross’ fifth graders took to audit their school’s waste; to better understand their food system; and to spread their findings and make change in their school and community. Use these steps as inspiration for involving your own students in climate action through food.

Researching the Problem and Connecting to Global Issues

Fifth graders at Marion Cross identified a problem: their school produced a lot of food waste. On par with the average American, students tossed one-third of the food they were served. Compost buckets overflowed with all kinds of scraps, and often entirely uneaten items. With further investigation, the problem got more complex.

Students learned that their food waste was often highly contaminated with non-compostable items like wrappers and plastic bags (pictured). The group also discovered that their waste was being used to make compost that “caps” landfills (i.e., covers trash). “This was definitely not the spirit of our composting efforts,” says Morley.

Students learned that their food waste was often highly contaminated with non-compostable items like wrappers and plastic bags (pictured). The group also discovered that their waste was being used to make compost that “caps” landfills (i.e., covers trash). “This was definitely not the spirit of our composting efforts,” says Morley.

Morley and Burkhart’s fifth graders learned about the environmental impacts of food waste on soil health and watersheds, and why composting matters. And they made connections between other topics they’d explored in science class—nutrient cycling, eutrophication, ecosystems, and decomposition—back to the food system.

Students were fired up, and they developed a hypothesis: Education about food waste for students and staff plus improved food quality in the cafeteria would result in less waste. In students’ words: “We could then compost or divert the waste we do produce, and help save the planet!”

Collecting Quantitative and Qualitative Data

To quantify the problem, fifth graders conducted a food waste audit using EPA guidelines. They collected two weeks of data on lunch food waste, categorizing and weighing every item that was thrown out compared to the total weight of food served.

There was qualitative data collected, too: Students conducted post-lunch interviews with their peers as they exited the cafeteria to better understand which items were most popular, why items were thrown away, how students would rate the quality of food they were served, and how they’d suggest improving school lunch.

The data showed that, in one student’s words, “We make a lot of waste.” Students eating school lunch—about half of the 337 students at Marion Cross—generated 60 gallons of compost each week. Add in waste from lunches brought from home, snacks, breakfast, and kitchen prep, and the amount only grows.

The data showed that, in one student’s words, “We make a lot of waste.” Students eating school lunch—about half of the 337 students at Marion Cross—generated 60 gallons of compost each week. Add in waste from lunches brought from home, snacks, breakfast, and kitchen prep, and the amount only grows.

Meeting with School and Community Partners

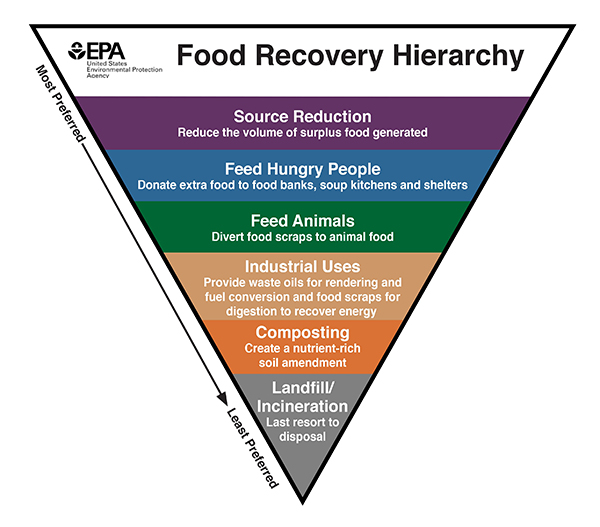

To inform their next move, students consulted the EPA’s food recovery hierarchy, which prioritizes the actions organizations can take to prevent and divert wasted food. “When you look at the hierarchy, we know composting is not the complete answer. What you really want to do is to not produce so much food waste to begin with,” explains Morley.

Students formed an environmental club so that they could devote more time to working on the problem. The group interviewed Marion Cross’ food services manager to better understand school lunch requirements and guidelines. “Food systems are complex and highly interrelated, so building a strong team for this kind of work is essential,” Morley says. The conversation revealed an opportunity to educate students and staff about food waste, and to shift to “offer versus serve.” In food service, “offer versus serve” is the difference between offering students a choice of what goes on their tray (while still meeting nutritional guidelines) rather than loading all available food options onto their plate. Offering instead of serving can dramatically reduce food waste.

Based on their findings, the club generated a list of recommended next steps—and presented their ideas to the Norwich school board. Says student Stahv of the experience, “I really liked how the environmental club brought lots of different people together around a shared passion: saving the Earth! And I like making presentations to people outside of the school about our work, especially to the school board.”

“We teachers could have presented to the school board, but because the kids did the presentation, it was heard so much more loudly. They spoke with such passion, and they were so fired up,” says Morley. “For them to feel like their voices have been heard on this issue was great…students’ voices really do have power.”

Taking Action

The school board and food service staff listened, and changes began to happen quickly, including improved communication and clarity in the cafeteria around “offer versus serve.” Says Morley, “Starting the next day, kids were offered a clearer choice for what went on their tray.” Students also launched a peer-to-peer education campaign about why food waste matters, what choices they have for what goes on their tray, and what belongs in the compost.

There’s a major shift underway in how Marion Cross composts, too: Rather than sending the majority of their waste across state lines, Morley and her students are working with Vermont master composter Cat Buxton through the Upper Valley Super Composter Program to establish an advanced composting system right on school grounds. Marion Cross is one of ten schools in the region to get a post-and-beam structure, large capacity compost bins, and material support and expertise. When it’s completed in 2025, the structure will handle all campus food waste. “The compost we make will be used to grow more food, allowing us to come much closer to our goal of ‘closing the food loop,’” explains Morley. In addition to the cafeteria, every classroom is now composting; fifth and sixth graders help empty the compost around the building into the on-site system every day. “I like getting my hands dirty with the compost!” shares student May. “I love food, so that feels important.” Adds student Etta, “I am most excited about teaching other kids at our school about the stuff we’ve learned, like how and why to compost.”

Another significant shift implemented at Marion Cross this year was flipping the school’s schedule to put recess time before lunch. “That was a huge identified source of food waste, that kids were throwing away almost their entire lunch in order to get out to recess,” explains Morley. Research confirms that this simple schedule switch helps increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Morley says collaboration continues with food service staff to get more local, culturally-relevant, and kid-prepared food in the cafeteria. Occasionally, students will harvest items from the garden and prepare them for the cafeteria’s salad bar, like basil pesto and pickles; the principal will give these items a shout-out in morning announcements. And, the school just received a grant to support getting more locally-grown, kid-prepared foods in the school lunch program.

The work continues this school year and beyond. Morley aims to redo the food waste audit with students to see how they’ve moved the needle, and report the results back to the school board. She’s also exploring ways to get unserved food to local families in need, and to local farms to use as animal feed. On students’ wishlists for the coming year: getting chickens to help eat food scraps, adding more vegetarian choices to the lunch menu, and taking a field trip to see a larger composting operation in action. “I’m really excited to be part of the compost project and I’m proud that the work we did in the environmental club made that possible,” says student Theo M.

“We still have work to do, but we have a team that feels mutually supportive,” Morley says. “It’s exciting to see the progress.”