Since working with Dana Bishop, Manager of Natural Resources and Forests, at Shelburne Farms. I see trees as one of the original citizens on the planet. They help the planet more than humans ever have. Learning about Nature in the outdoors with Dana, facing Nature directly and being able to touch it with all my senses, I feel inexplicably alive. Learning about Nature in the outdoors should be part of every curriculum beginning at the earliest age possible.

What the Forest Can Teach Us

Highlights from A Forest for Every Classroom 2023–24

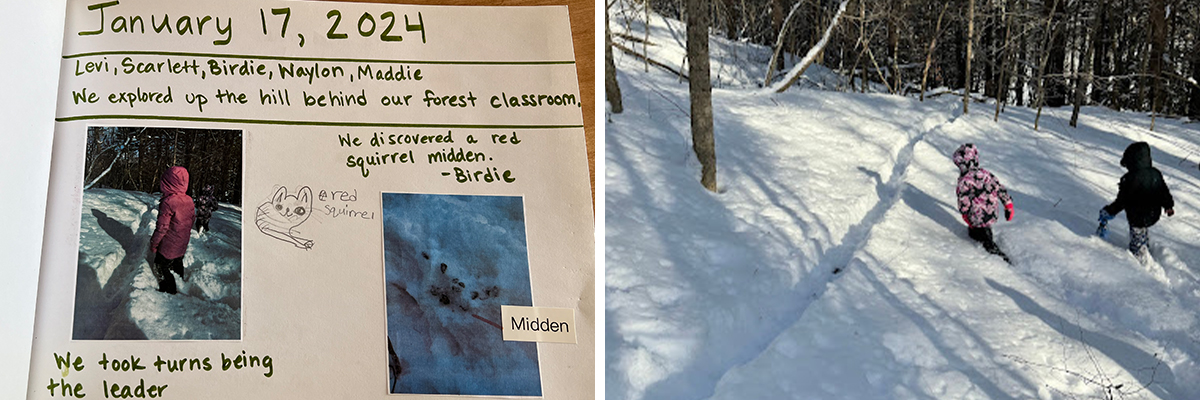

It’s mid-January in Tunbridge, Vermont, and the snowy woods behind First Branch Elementary School look still and lifeless—that is, until you slow down and investigate.

“Miss Caitlyn! Miss Eliza! Midden! MIDDEN!” shouts a second grader, crouched at the base of the tree. A half dozen students come running to take a closer look. Sure enough, a Red Squirrel has created a cache of seeds and stems, called a “midden,” in this spot. The group read about the habits of these tiny forest residents earlier that day, and they can’t believe their luck.

These expeditioners are led by teachers Caitlyn MacGlaflin and Eliza Minnucci. Across the seasons, second graders seek to answer the question, “Who is the forest?” In the classroom, they read about the area’s plants and animals, building background knowledge; in the forest, they explore, identifying everything from animal tracks to tree bark to invasive plants. Later, they record what they’ve noticed—and what they’re still curious about.

Caitlyn and Eliza developed this course inspired by their experience in A Forest for Every Classroom, a year-long professional learning program with Shelburne Farms Institute for Sustainable Schools, The National Park Service Stewardship Institute, and the US Forest Service. “During this year, I've moved quite a bit further in my teaching practice, from teaching in nature to teaching with nature, from lessons about counting branches on trees and doing read alouds inside, to exploring and discovering and observing and recording outside,” says Eliza. There are, of course, many more outcomes than discovering squirrel middens; these lessons meet dozens of standards in literacy, science, math, and global citizenship.

Crucially, students are developing habits of observation and reflection, and a sense of connection to and responsibility for their place. These are the underlying ideas of A Forest for Every Classroom: Learning to Make Choices for the Future, which just concluded a year of convening teachers for transformative learning. “These outcomes are unique to taking students to the forest—they happen because we’re going outside, and because we’re opening up to experiences as they unfold,” says Caitlyn, a second grade teacher. “Spending time with like-minded and passionate educators and experts through A Forest For Every Classroom helped to reinvigorate my own values and improve my outdoor teaching practices.”

Read on to hear a few more stories from the 2023–24 cohort.

Sandra Fary, grades 7–8 science teacher in Richmond, Vermont

Her ongoing work: Sandra immersed her students in a variety of forests throughout the year through field studies. Together they participated in a fall bioblitz, taking inventory of all of the tree species on their school campus. Later, they learned about floodplain dynamics, a vital topic in the face of increasing extreme weather events. “The town I teach in was really hit by summer flooding. So, we looked at the power of water and what the forests that border our rivers provide for wildlife and for flood management,” she explains. Next year, she’s aiming to incorporate more Indigenous perspectives, inspired by speakers and readings in this course, and to forge new partnerships with forest researchers in the area.

On why this work matters: “My main takeaway is that the more students know about forests and our interconnectedness, they’ll feel more connected to their place. They are going to be better decision-makers and stewards of our land, and are more likely to conserve and protect Vermont. Also, mental health is huge. Getting kids outside and connecting them to the natural world really helps.”

In her words: “I can’t say enough about this course. It’s influenced my pedagogy in every way. It instilled confidence, provided me with resources, and connected me to colleagues and the landscape.”

Kellie Hallock, first grade teacher and Mandy Walsh, school librarian and farm to school educator in Westminster, Vermont

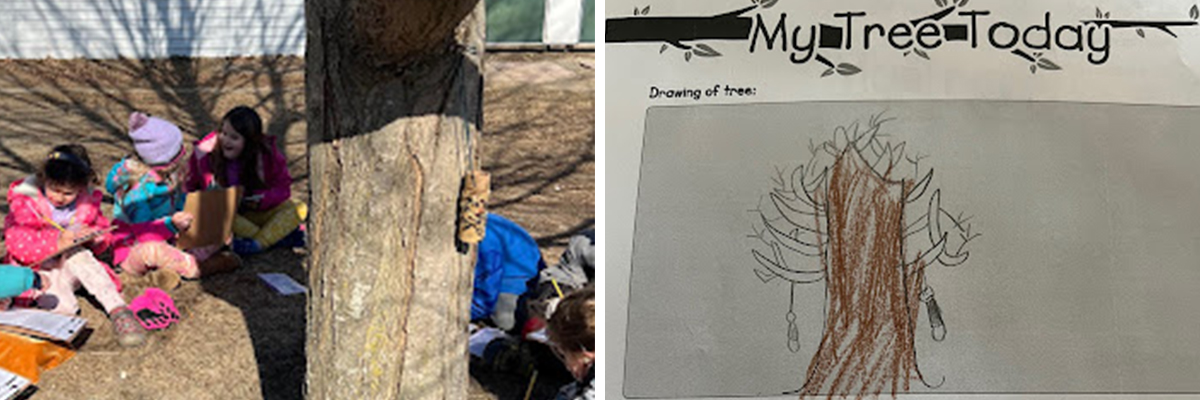

Their focus: Kellie’s first grade class typically spent just one half-day learning outside with Mandy. Kellie’s goal was to bring outdoor learning into more of the school week, even if they couldn’t be outside. This started with students answering a single question: What type of tree is outside our window? “We have a gorgeous maple tree right outside our classroom,” explains Kellie. “So students can sit at our writing table, study the tree, and in that way we can learn about the forest all week long.” The maple tree became the center of an entire year-long unit, connecting to science standards around patterns and seasons. First graders learned about parts of a tree; how trees are similar and different; and how trees are important to all living things. For Mandy, it’s also about learning how to ask questions: “My goal with everything is to have kids start to ask questions. If kids can learn how to ask questions about things, they can begin to get curious, to figure out what they care about, and learn to build a life that they love.”

On thinking differently outside: “Through this program I saw the value in students learning how to identify a tree, and learning about our outdoor classroom, not just learning in our outdoor classroom,” says Kellie. “Tree identification has shifted and changed my life. I sound dramatic, but it’s true. Being in the woods is so much more meaningful for me now. The curiosity it’s brought me, the challenge of something new, has shifted my own thinking outside.”

Andrew Njaa, high school physics teacher; Margaret Sobol, outdoor learning educator; and Justin Deri, farm to school program manager in Falmouth, Maine

Their focus: This interdisciplinary team hatched an idea for utilizing a 40-acre piece of forested land at the center of their district’s school campuses. “Our big project was to find a way for all of the grades in our district to use this land, incorporating many different aspects of what we already do as outdoor educators,” explains Justin. Inspiration struck when a team from Woodstock Union Middle & High School’s CRAFT Program visited as guest speakers. Says high school teacher Andrew: “What inspired me is that the CRAFT credential model brings teachers from any academic discipline into the fold. Suddenly a stats teacher or a foreign language teacher can create curriculum that is centered in an ecological, outdoor space and have that be part of a larger experience for students. The teachers themselves are then creating a larger community within the high school that honors and includes the world literally outside the walls of the school.” The Falmouth crew has since created a proposal for a year-long interdisciplinary program in which students will learn on and with the land, and will continue this work over the coming year as part of the Education for Sustainability Leadership Academy.

On practicing curiosity: “Many of our current high school students are very academically-driven but don't have a relationship with the natural world,” says Margaret. “We hope to build stamina for learning outside and connecting with the natural world as our students move through the K—12 continuum. So we're hoping to inspire curiosity when students are younger and nurture that as students age up.”

Their motivation: “All of this work is really about climate resiliency, and creating connection to the environment, so that our students may know it, and if they know it and understand it, they will care about it, and if they care about it, then they will work to protect it and have the tools to do so,” explains Margaret. Adds Justin, “Care leads to protection.”